Nine Silos Have Dismembered Comprehensive Planning

Comprehensive planning has a robust history, with differing methodologies emerging from various ideologies and historical movements. For the past two decades, however, most planners in Wisconsin have employed a singular approach for developing comprehensive plans. This approach is based on the Smart Growth Law, which outlines nine elements that must be included in such plans. These nine elements have been treated as disjointed categories – separate chapters with separate goals, separate analyses, and separate recommendations. This approach has, in effect, made comprehensive planning incomprehensive. It is time we reclaimed professional planning practices and returned to well-founded traditions for understanding our cities, villages, and towns, based on the collective day-to-day experiences and sensibilities we have shared for many years.

Comprehensive Planning Must Begin with the Holistic View

Reliance on the nine elements required by state statutes has allowed comprehensive planning to become automatic and complacent. Instead of beginning the planning process with an attempt to understand the unique characteristics and qualities that define our cities, villages, and towns, the nine-element approach begins with predetermined lenses that pretend to capture the whole picture. With these narrow lenses, many critical problems remain on the sidelines (e.g. health, social justice, education, place-making, climate uncertainty, market trends, capital budgeting, resilience, etc.). We need to stop these dysfunctional habits, disrupt our practices, and think again. How can we develop comprehensive plans that respond to unique local needs, conditions, and opportunities? How can we dissolve the boundaries of our analytical approaches to generate holistic understandings of our communities?

Define the Community with Named Places – Neighborhoods, Districts, Corridors

For many planners, the inevitable starting point requires mapping the cultural geography of local neighborhoods, districts, and corridors. The Charter of the Congress for the New Urbanism calls neighborhoods, districts, and corridors the “essential elements of development and redevelopment in the metropolis. They form identifiable areas that encourage citizens to take responsibility for their maintenance and evolution.” Many other critics and practitioners have used similar modes of thinking (Jane Jacobs, Kevin Lynch, Christopher Alexander, Jan Gehl, Gordon Cullen). While these theories have wide differences, they all have empirical foundations based on longstanding geographic places with local names and histories. Moreover, these well-argued, well-respected theories never rely on the abstract geometric jurisdictions of census tracts, political districts, big data, and certainly not the nine silos we use. We must make plans based on real places.

Enable Public Understanding with Place-Based Language

In what places does the local population live, work, and play? Do they live in H3, work in C2 (but some work in MU special district V), and they play in the right-of-way and I-2 districts? Is it any wonder that many people do not appreciate land use planning? Our comprehensive plans should not begin with jargon-based abstractions but with land uses defined as the named places of our everyday lives. Example: they live in the Eastown, work in the Riverfront Arts District or Downtown, and play along Main Street or in Central Park. Meaningful places and their activities must be implied and named from the bottom-up, not theorized from the top-down.

Marry Regulations to Real Places, not Abstract Categories

Named places should include specific regulations for social and economic activities – the difference is these regulations should relate to real, contiguous places, not to abstract zoning categories. Setbacks, for example, should be customized to fit each neighborhood, rather than applied in cookie-cutter fashion to different residential areas. A place-based land use map can easily include customized regulations for visual character, circulation, environmental preservation, resilience, and so forth. A “uniform” code applied to an entire community can become a straitjacket, whereas a “tailored” code can more comfortably fit the unique local conditions within each sub-area. In our experience, we have managed to avoid major disagreements when we create plans that reflect a common understanding of the neighborhoods, districts and corridors that the comprise the local community.

So How Should Planners Do this?

Balance Quantitative Analysis with Observable Common Sense

Focusing plans on neighborhood, district, and corridor allows us to balance pragmatic methods and valid theory. Back in 1972, a Milwaukee community group (the Eastside Housing Action Committee – ESHAC) developed a neighborhood plan for the Riverwest neighborhood. At that time, the local government planners had statistically divided the area into two halves – one half worthy of City funds for revitalization and the other half not worthy of investment. The ESHAC neighborhood plan rejected this method and assessed the area as a single community – consistent with observable common sense. The City argued that this “west-of-the-river” neighborhood could not retain a unified identity based on empirical, yet qualitative judgements, because it violated the City’s methodology. The problem then, and today, is that plans all-too-often place blind faith in quantitative analysis and ignore observable common sense. Statistics help, but cannot replace the talent and insight needed to plan for the ambiguous, uncertain nature of evolving populations.

Create a Vision for Each Place

Crafting place-based land use maps requires thoughtful analysis of cultural geography. Physical geography (soil, topography, natural ecology) are all influential, but not deterministic. Rural townships and dense urban areas all have different stories to tell, which means planners must define local places using that local knowledge, behavior, and history. In one community a neighborhood may be just four blocks of dense housing, while in another a neighborhood might be a square mile. Each place will have different opportunities and challenges to be defined using bottom-up inferences, not abstract categories or standards based on non-comparable communities. One size is convenient, but never fits all places. Customized, bottom-up plans can unfold quickly from local observations:

- What types of development really fit in each neighborhood, district, and corridor?

- How much change or stability should be recommended in each subarea?

- Which places need economic development, social change and/or environmental improvement?

- Are our neighborhoods, districts, and corridors resilient? Can each withstand disasters?

Develop a Detailed Framework for Each Place

As answers pour forth, planners can frame the details for each area using typical methodological tools like matrices, diagrams, lists, and simple narrative descriptions. This method allows the internal aspirations of the community to be revealed for each subarea, allows comparative planning, and helps minimize conflicts. In addition, each subarea can be linked to zoning categories using terms like “desirable,” “allowable,” and “undesirable.” These terms resonate intuitively with citizens and avoid use of jargon (such as “permitted” or “conditional” uses, “variances”, etc.). One neighborhood, for example, might like retail uses but not large format stores, while a nearby business district might have the opposite view. These different views need not conflict with each other – planners can easily show how one place-based land use subarea can vary dramatically with another.

Use Organizational Silos for Implementation

As a place-based land use map begins to take shape, questions of implementation (and resource allocation) should be defined. This is the moment when “silos” become highly relevant. Each place-based land use will require resources from different “silos” – the departments and agencies from local government as well as outside organizations (state, county, private, and not-for-profit sectors). Ironically, many planners avoid this specificity just when it is needed the most. Typically, there are four categories of actions for different “silos”:

- Programmatic actions that make something happen (BIDs, TIDs, etc.)

- Regulatory actions that constrain actions (zoning, street requirements, and other codes)

- Resource expenditures to make community investments (capital improvements and operating expenses)

- Management changes to reassign accountability and responsibilities

Place-based plans can easily identify the actions needed for implementation within each subarea. One neighborhood, for example, might need a change in traffic patterns while another district may need a change in zoning; a business corridor might need a TID district and an innovation district might need staff support. Without down-to-earth, geographically located, and community-vetted actions, the comprehensive plan quickly becomes a plan that sits on the shelf, only to be replaced by an update several years later.

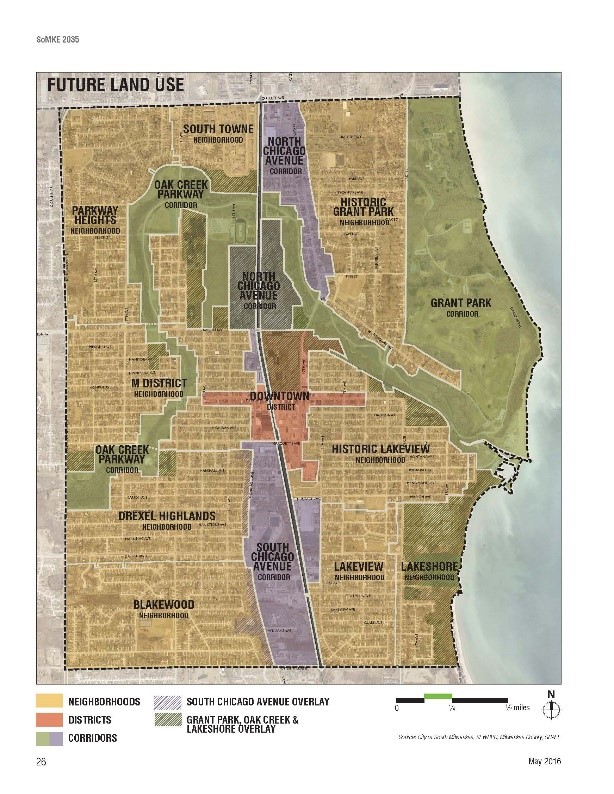

South Milwaukee’s recent comprehensive plan organized all land use regulations within a place-based map. Each named neighborhood, district or corridor included customized recommendations for desirable, allowable, and undesirable uses, as well as visions for future visual character, circulation, and related environmental needs.

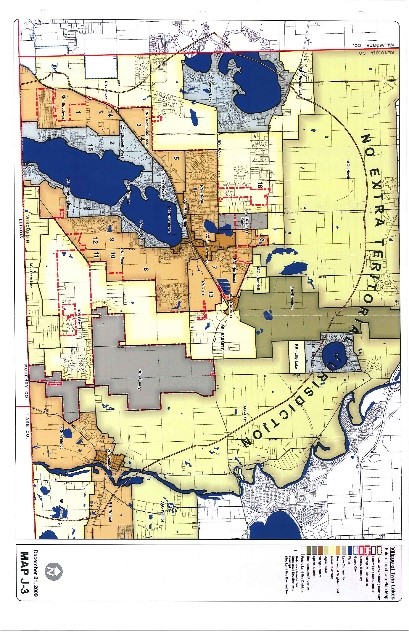

The Village of Twin Lakes adopted a placed-based land use map as a user-friendly way to define individual types of buildings, differing expectations for traditional waterfront housing, locations for village commercial districts, and growth areas for rural districts.

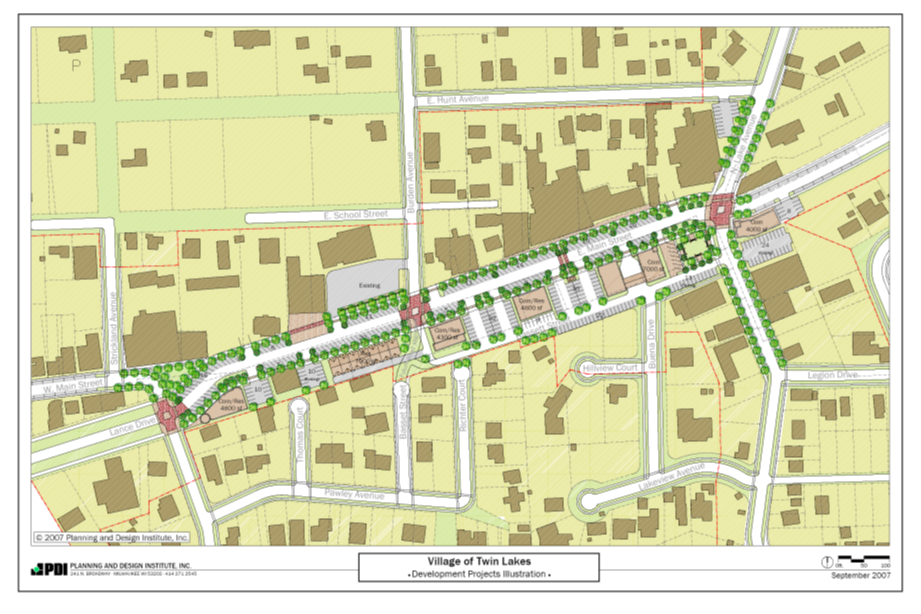

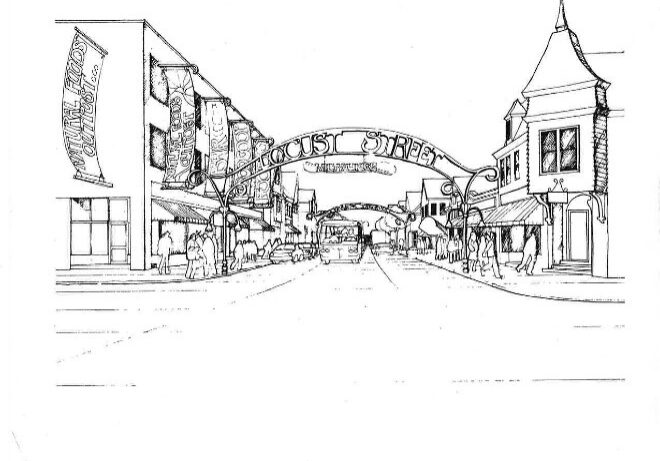

The Village of Twin Lakes implemented a key component of their place-based land use plan by revitalizing their traditional main street, including new redevelopment (the first in years) and new streetscape – both designed in a consensus-based process.

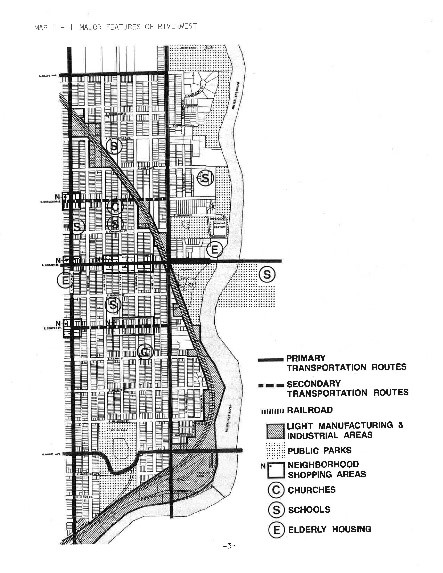

Today, Riverwest is a thriving, diverse neighborhood in Milwaukee. Back in 1972, however, the City wanted to split the area and provide revitalization funds to only one half of the neighborhood. After this plan was stopped and replaced with a locally sponsored neighborhood plan (as shown in these two illustrations), the area began to improve and today represents a true success in placed-based neighborhood revitalization.

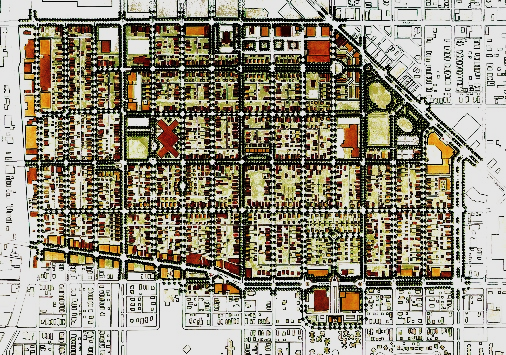

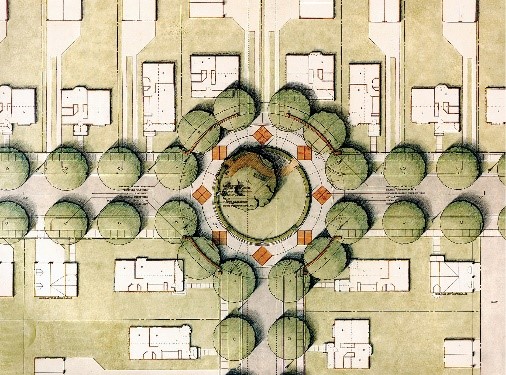

These three illustrations show a typical sequence of place-based planning in Milwaukee – an overall neighborhood plan (for Midtown) identifying locally derived needs and options, an achievable design for high-quality residential development (called City Homes), and the final outcome using new city infrastructure to frame high-value, diverse single-family homes.