Solving the Dilemma

Have you ever been frustrated that your new technology doesn’t fit nicely with your existing setup? It’s the same phenomenon as when a new development project needs a curb cut, parking lot, service entrance, lift station, stormwater pond, or any other piece of infrastructure that was left out during the planning stage. It doesn’t have to be that way. Good infrastructure planning for innovative, high-value, or complex development requires forethought and creativity. Too much infrastructure wastes resources, while too little wastes opportunities. We think this dilemma can be solved.

Enable Multiple Scenarios with One Infrastructure

“But how does it fit the market?” This anxiety represents an all-too-common sentiment expressed by officials when discussing plans for major new developments. Despite the desire for predictability, typical market analyses conclude, as they should, with a variety of potential scenarios. This variability is unavoidable – the future will always be uncertain. When reviewing these analyses, communities must not make the mistake of selecting their favorite “vision” for the future, as if ordering a meal from a menu. Instead, communities should focus on creating the underlying conditions (i.e. the infrastructure) that would enable a range of preferable outcomes:

- Should new residential units be townhomes or apartments?

- Should buildings be high-rise or mid-rise?

- Should parking be underground?

- Should we plan for supporting retail?

- Should we plan for a grocery store?

- What about mixed-use?

A good infrastructure plan will allow for many scenarios, for multiple combinations of scenarios, and, most importantly, for changes over time. This dilemma is nowhere more critical than in the design and engineering of new infrastructure for large urban redevelopment districts.

Create a Comprehensive Collaborative Team

Dovetailing infrastructure with urban development requires careful customization to local conditions. Infrastructure is not a “plug-and-play” commodity, but an interwoven set of complex systems. Engineers, planners, landscape architects, and property development professionals must coalesce into a team with strong local knowledge regarding:

- Streets, sidewalks and parking

- Trails, bike systems and pedestrian routes

- Multiple transit systems

- Service and delivery systems

- Water distribution, wastewater and stormwater management

- Gas, energy and electrical power

- Safety, fire, security and emergency systems

- Waste disposal

- Fiber optic and communication systems

- Management technologies and human resources

Allow for Flexibility in Implementation

It is critical that the implementation framework allows for multiple urban design and redevelopment options – each of which may be preferred for different reasons. That is, while there may be more than one type of development that will help achieve the City’s goals, all the options should fit within one infrastructure framework:

- The infrastructure framework should encourage incremental redevelopment on a block-by-block or parcel-by-parcel basis while maintaining a fixed overall pattern.

- The framework should enable each investor to see different combinations of solutions and allow for different approaches.

- The framework might have several preferred first projects, but all approaches must follow the same infrastructure plan.

- The first project must not restrict future opportunities – it should encourage continuing development.

- All options should be workable with a substantial variety in the types of buildings and parking systems adopted by developers.

Plan Infrastructure for the Long Term

For decades, suburbs have planned new infrastructure to fit the “first-site occupants” and ignore long-term consequences. This led to infrastructure solutions that encouraged the sprawl of the last decades. This pattern of development is no longer sustainable – for suburbs or cities. We must broaden our focus to emphasize long-term priorities – whatever works for the “first-site occupants” must not be the only consideration for new infrastructure:

- Infrastructure plans must consider what might be carried forward for the second user.

- Infrastructure plans must consider multiple scenarios for development (perhaps high, moderate, and low density) – such an approach will naturally evolve into a long-term plan with multiple possible outcomes.

- Long-term scenarios might include unproven visions and emerging markets (e.g., high density, high-value buildings) along with more pragmatic, lower risk options (e.g., low density, moderate-value buildings).

- Scenario planning must allow for different concepts to occur at different times in different parts of the same district.

- Scenario planning must not by myopic - designing infrastructure to support only ideal approaches rarely succeeds and often makes matters worse.

Design Sustainable Streets, Blocks & Lots

Major investments in infrastructure do not come every year, or even every decade. Planning infrastructure for the long-term must focus on reducing a community’s long-term risk and increasing their potential rewards. Thus, the goal of new infrastructure should be on creating sustainable systems that enable a wide range of possibilities. To this end, new streets, blocks and lots should represent a logical continuation of the existing infrastructure systems – both in form and function. Grandiose, dramatic interventions into the urban fabric may be exciting and compelling, but often lack a long-lasting potential for adaptation to change. The key is to allow variations to occur over time in response to social, economic, and environmental conditions:

- The most sustainable systems use simple, small-scale geometries that can adapt to a broad range of needs and conditions.

- Most commonly, cities employ locally customized grid systems to maximize the possibilities and maintain adaptability.

- New designs should avoid arbitrary or overly subjective concepts – visual diversity is best achieved incrementally through architecture and landscape rather than civil engineering.

- Deviations from grid geometries are also necessary, but not as a primary organizing framework. Occasional deviations from the norm are welcome – especially when making civic plazas and great public places. That is, street, block, and lot plans need to include both the geometry of “exceptions” and the geometry of “rules.”

Customize the Regulatory Framework

To enable the implementation of an infrastructure plan, the City needs a regulatory framework – often involving overlay zones, specialized codes and/or planned development districts:

- Within the regulatory framework, a single infrastructure system should be adopted that specifies the location of the circulation network, utilities, public places, and related features.

- The regulatory framework should enable infrastructure systems to be implemented incrementally, block-by-block and parcel-by-parcel, in response to developer investments and available funds.

- Conversely, the framework should allow for the development of larger increments, depending on financing and resources.

- Most important, the City must ensure the certainty (i.e. political support) of the infrastructure system in order to create a lower risk investment environment for developers.

Illustrate Broad Architectural Diversity

Variety is the spice of life – site design illustrations should show variation in how building types are located, how parking is accommodated, how public places are designed, and how site guidelines are applied. Most often, it is advantageous to show investors multiple architectural styles and approaches in order to demonstrate the community’s openness to visual diversity. At the same time, it is essential to show investors and developers that the potential visual diversity works cohesively and fits within the long-term infrastructure pattern and urban framework.

Collaborate with Each Developer

It is unlikely that every investor and developer who comes to the table will have the same missions, goals, and values. Demonstrating to these future stakeholders that the City is committed to accommodating a diversity of activities and uses is critical for creating dynamic, long-lasting places. Similarly, some investors will want to use their own architects, designers, landscape architects, and engineers – others may look for suggested consultants who can work with the city effectively. All these action models should be accommodated.

The plan for Waukesha’s downtown and neighborhoods demonstrated multiple development scenarios along the river’s edge. These three options show different concepts for buildings, parking, and public places – all of which fit into the same infrastructure pattern. The different development scenarios responded to local stakeholders and interest groups with diverse priorities for social and economic outcomes.

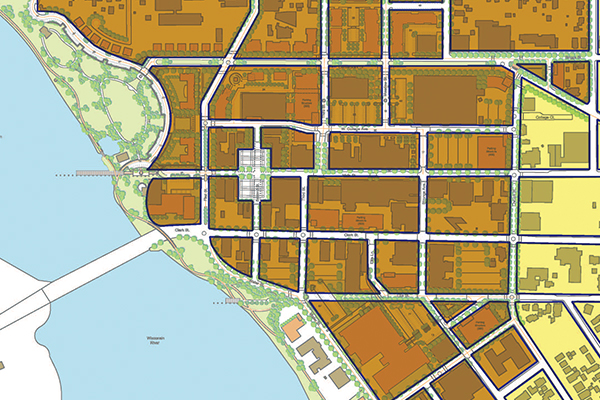

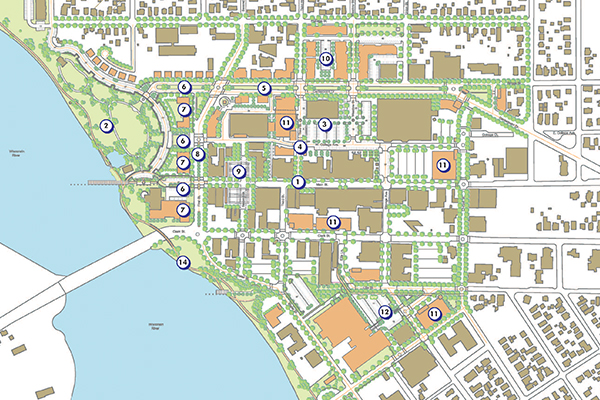

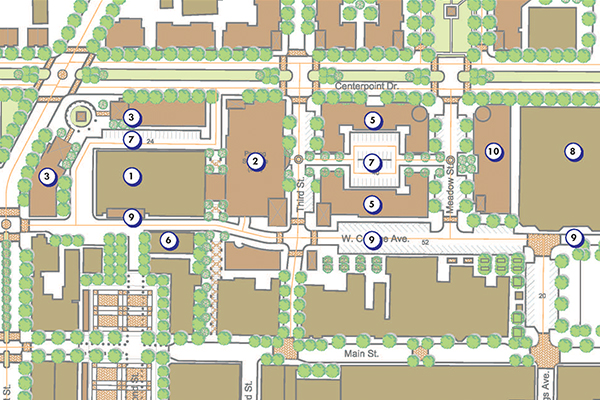

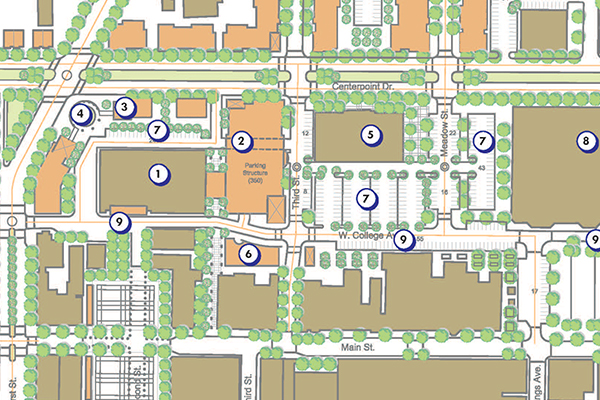

This plan for the revitalization of Stevens Point’s downtown shows a sequence of decisions from the street and block plan (top), to a full build-out of new development (second from top), along with two options (below) for redevelopment of a defunct downtown shopping mall that was no longer economically viable. Both options follow the same basic infrastructure plan based on extension of prior grid systems that existed before the mall was constructed.

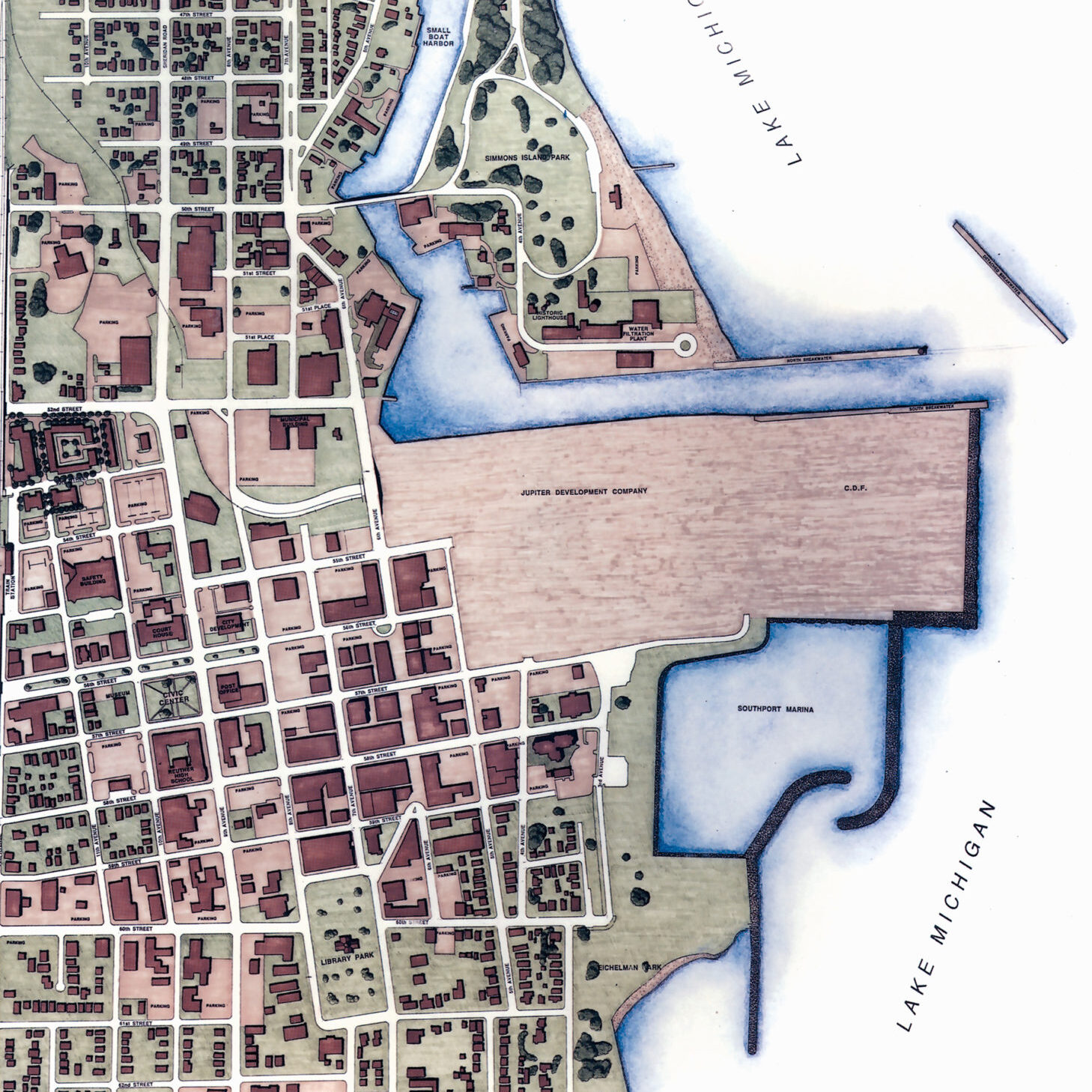

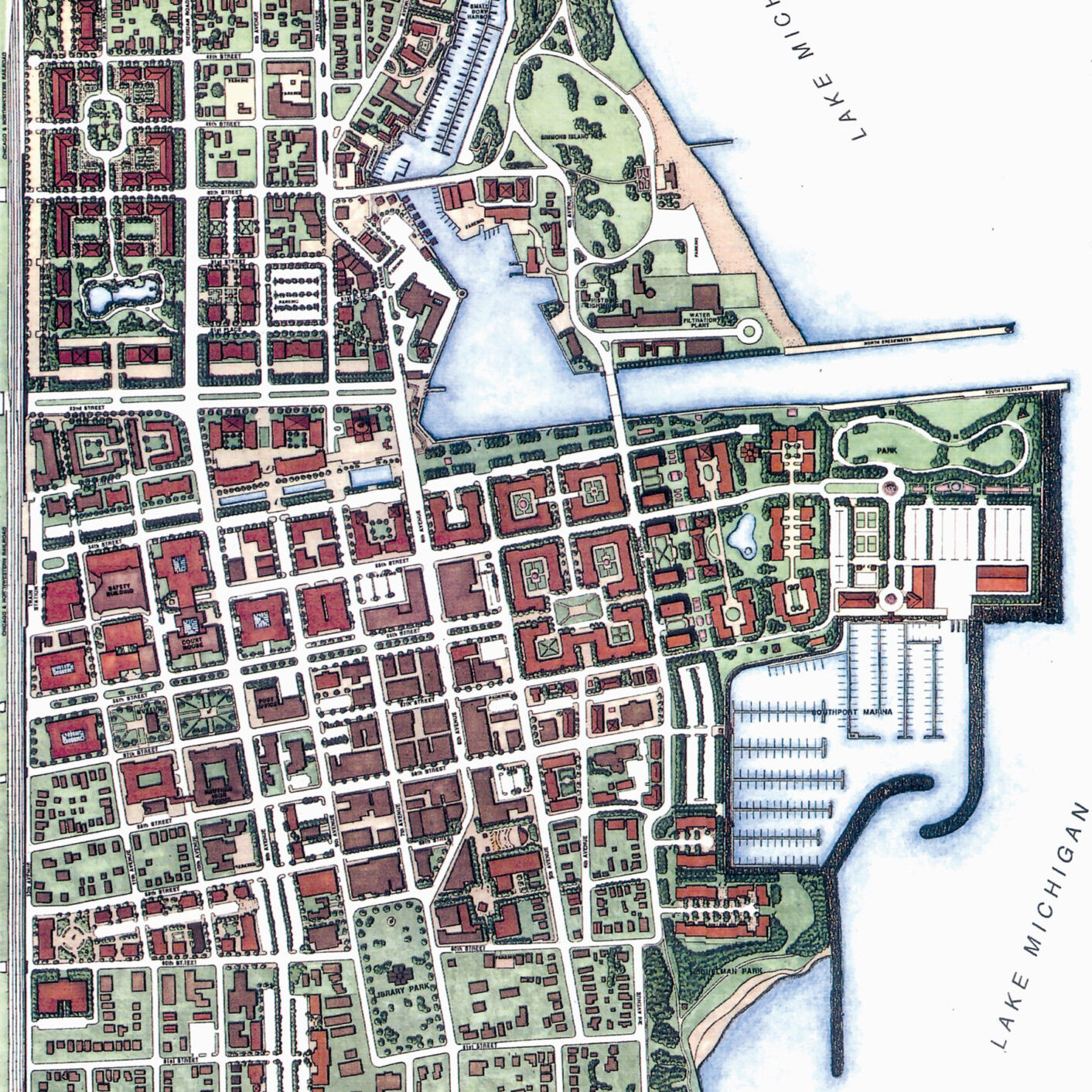

Kenosha’s Downtown Plan expanded the grid system from the City Beautiful movement. The 1991 plan created a strong formal pattern that, over the next 30 years, set the framework for diverse architectural styles and civic buildings. A strong, simple infrastructure plan created the framework for integrating different projects, uses, and public places.

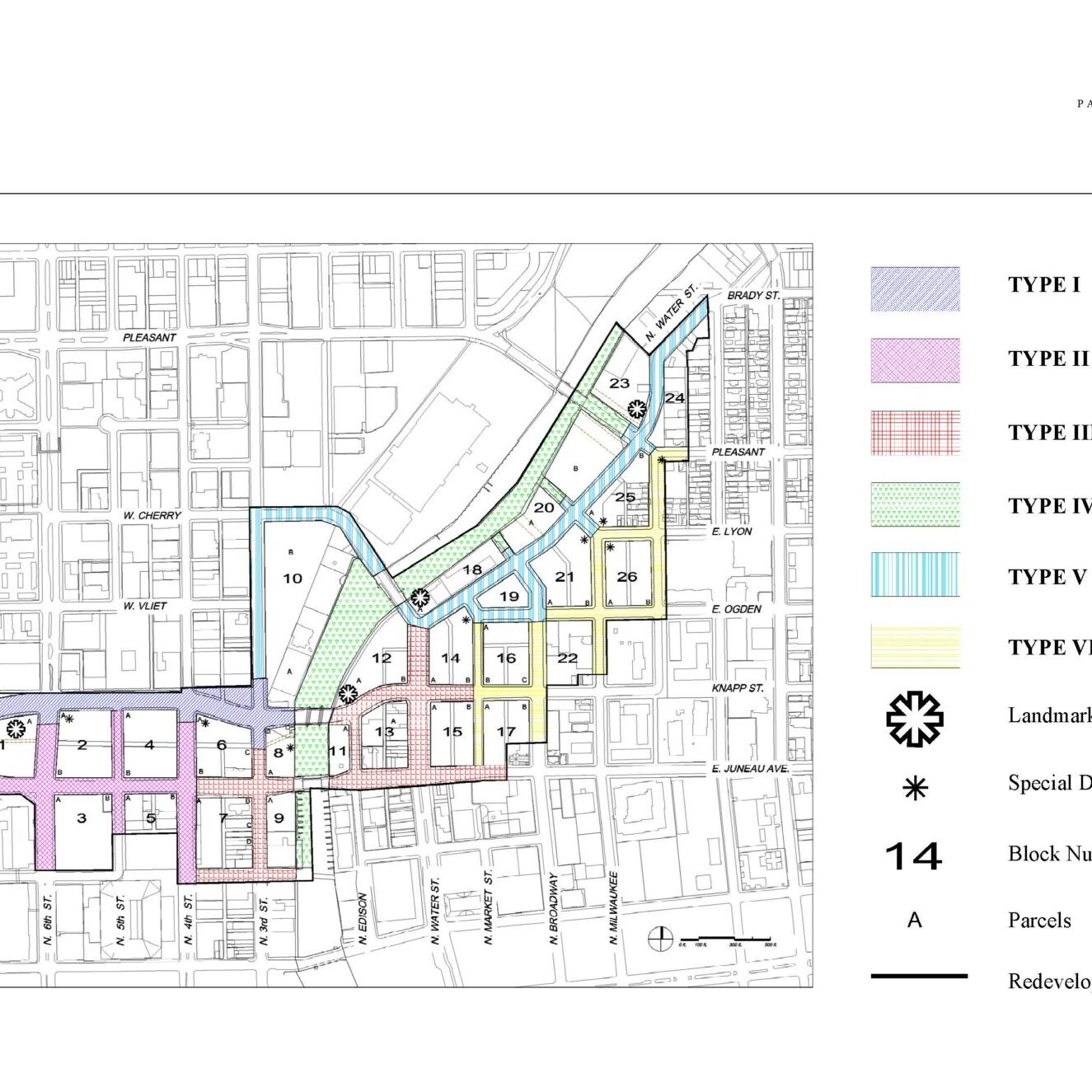

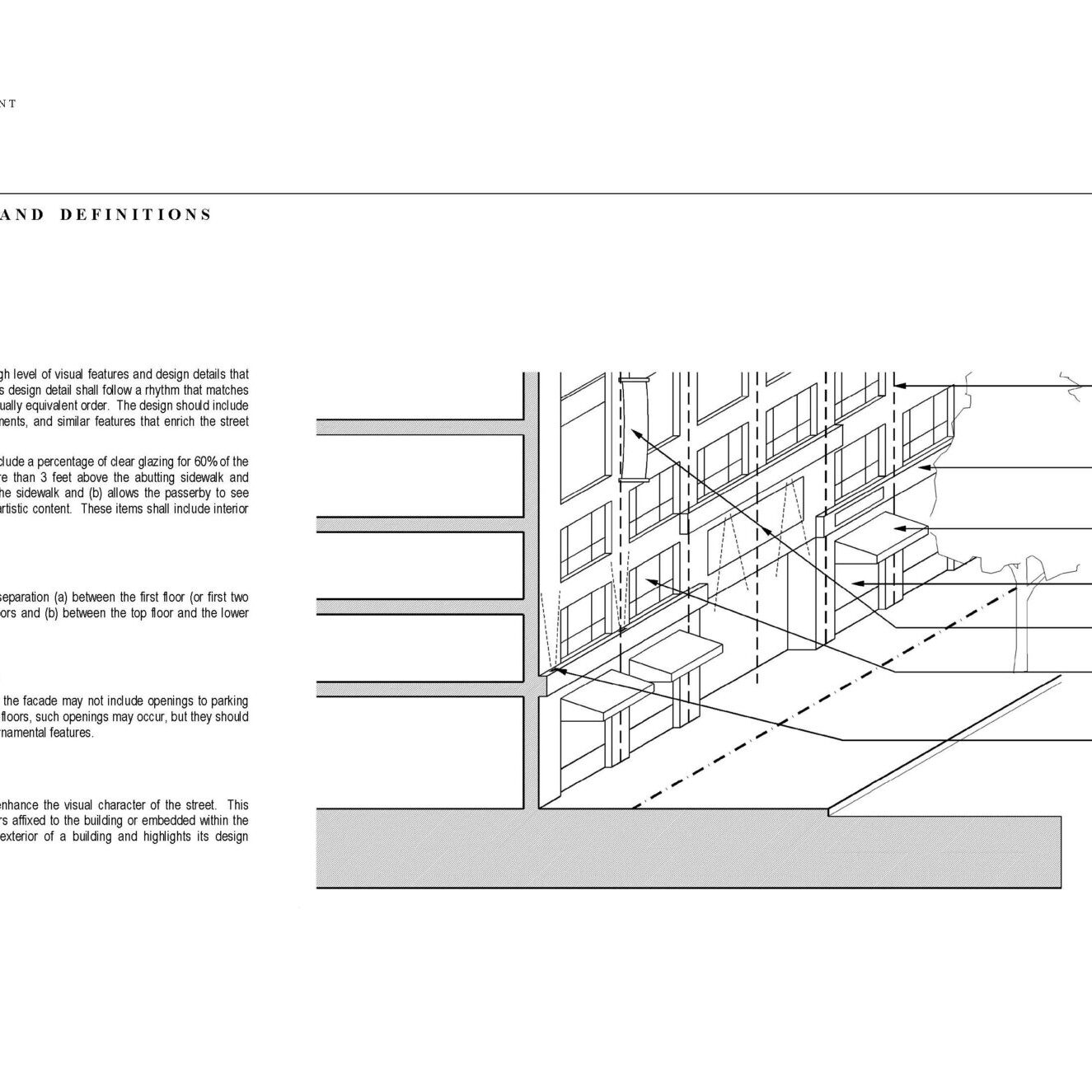

Milwaukee’s Park East Redevelopment Plan replaced a freeway and extended the prior street and grid infrastructure. This plan framework – intended for a 20-year build out -- reestablished the prior infrastructure and enabled multiple architectural concepts that fit into one framework. The plan also used guidelines created for:

- Each type of street shown in the colored areas (top illustration)

- Architectural diversity and street activation along building facades (bottom illustration)